Introduction

With increasing health awareness and interest in Japanese culture, Japanese cuisine has grown to become a global phenomenon. From large metropolises to small villages, it is not uncommon to find a Japanese restaurant, dish, or an ingredient influenced by Japanese culture—Kazakhstan is no exception. Since the country gained independence in the 1990s, Kazakhstan, with its abundant natural resources, has quickly developed to become one of the wealthiest and most stable nations in the Central Asia region (Sultanov 2010, 5).

Farrer et al. (2019) state that “Non-Japanese ethnic networks are especially important in spreading Japanese cuisine in low-cost forms away from urban centers,” but I postulate that this can be extended further to include countries with a small population of Japanese expatriates, such as Kazakhstan (40). Despite there only being 171 Japanese nationals living in Kazakhstan, many restaurants and dishes influenced by Japanese cuisine are found all over Kazakhstan (Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2019). Compared to larger trends in the diffusion of Japanese cuisine observed in countries with a large ethnic Japanese population, the popularization of Japanese cuisine in Kazakhstan is distinct. I argue that the mobility of Japanese cuisine in Kazakhstan is facilitated by non-Japanese ethnic networks and can be characterized by the public perception of Japanese culture and non-Japanese businesses capitalizing on the demand for Japanese food.

This paper will briefly discuss the intercultural nature of Kazakhstan’s history, and how this serves as a cultural backdrop for Kazakh cuisine. This will enable for an examination of what types of food may become popular and eventually integrated into the lives of the Kazakh people, and thus assist the analysis of the expansion of Japanese cuisine in Kazakhstan. A special focus will be placed on the significance of sushi in Kazakhstan, demonstrated through social media advertisements and the use of oriental stereotypes. In addition, the sushi and pizza combination, a localized pairing in Kazakhstan, will be investigated. I postulate that sushi and pizza play a similar role, as a malleable foreign dish that has the potential to adapt and localize in a culture. Then, I will discuss the diverse roles an ethnic Japanese business may play in a region with a small ethnic Japanese population. Furthermore, the significance of non-Japanese companies on the presence of Japanese cuisine in Kazakh households will be examined. Finally, a discussion on the future of Japanese cuisine in Kazakhstan and broader implications of the cultural mobility of cuisine will be unpacked.

As a Japanese and American student living in Kazakhstan for sixteen months, my analysis is based on interviews with Kazakh people and a Japanese restaurant owner in Nur-Sultan, examination of supermarkets, restaurants, and malls, participation in cultural exchange events between Kazakhstan and Japan, social media advertisements, and my daily experiences and observations. My research will only focus on urban settlements in Kazakhstan, and most significantly the capital, Nur-Sultan. The urban to rural settlement ratio in Kazakhstan is approximately 3:2, with most of the urban population concentrated in Nur-Sultan, Almaty, and Shymkent (Britannica 2020). Therefore, the arguments made in this paper may not apply to all regions of the country, especially rural regions. Furthermore, it must be noted that all interviewees could speak English, as well as Russian and Kazakh. It is found that those able to speak three languages are generally of the upper-class, and thus it must be considered that their background has colored their perspective of the topics discussed below.

Background Information

That Kazakh population as of 2020 is approximately 19 million (Central Intelligence Agency 2020). Among these people, there are said to be over 120 ethnic groups, with the highest proportion being the ethnic Kazakhs (58.9 percent). Originally from Turkic and Mongol nomadic tribes, ethnic Kazakhs are said to have migrated to the region in the 15th century (Tredinnick and Dagmar 2018, 81). Due to the complicated history with the Soviet Union, ethnic Kazakhs can be found around the world, mostly in neighboring countries such as China, Russia, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Mongolia, Tajikistan, Turkey, Iran, and Afghanistan (Central Intelligence Agency 2020).

The majority of the Kazakh population are Muslim; however, adherence to religion has been informal dating back to the nomadic period. The Soviet rule further diminished the influence of religion in Kazakhstan and therefore, there is a strong drinking culture and more freedom in food that can be consumed. The influx of Russian and East European immigrants also led to the introduction of Eastern Orthodox ideologies into the region. Currently, about a quarter of the population is Eastern Orthodox (Britannica 2020).

- Kazakh History and Cuisine

The cuisine of a country is one indicator that reflects the larger capacity of a society to accept and interweave elements of different cultures into their own. With regard to Kazakh cuisine, the ethnic diversity of the country is clearly represented through its food. Throughout history, food from different ethnic backgrounds has adapted to the Kazakh environment depending on the availability of ingredients and to better suit the Kazakh palate.

The nomadic lifestyle relied heavily on various agricultural livestock such as cattle, sheep, yaks—horses being the most significant. Horses were vital for mobility as well as their value as meat and dairy source (Yemelianova 2019, 13). Horse meat and dairy products still remain staple foods in Kazakh households today. Due to the transient lifestyle, nomadic people used different ways to preserve and prepare milk and meat, their main source of food. One way was salting; it is said that in the past, one would place a piece of meat under their saddle, which would flatten and tenderize the meat as well as the horse’s sweat providing the salt. Although such salting methods are not used today, this may be a reason why many Kazakh dishes are still heavily salted.

Soviet Rule and Forced Collectivization

In all of the interviews I conducted, the Soviet rule was brought up as a focal point in the proliferation of different cultures entering the Kazakh culture. Russia conquered Kazakhstan in the 18th century and once again in the 19th century. In 1925, Kazakhstan officially became a part of the Soviet Republic. Mandates made by the Soviet Union that came one after another decimated the livelihoods of the nomadic population in Kazakhstan and many other Central Asian countries. It must be noted that recognition of current Central Asian countries as individual nations, and the creation of national borders was only established in 1936.

Forced collectivization had resulted in the loss of half of the Kazakh population. Abandoned areas were then populated with deportees, convicts, and settlers from the Soviet Union. At the brink of World War II, different ethnic groups that were suspected as enemies of Stalin were exiled in large groups: the Volga Germans, Balkans, Greeks, Koreans, Chechens, among many others (59). Many of these people either starved or froze to death, and only a portion was able to survive after being saved by the minimized Kazakh population. Although an understatement that diminishes the cultural destruction, one positive aspect that came about was the intercultural exchange. It was during this period when different ethnic groups came together to share their culture, resulting in the diversity of current-day Kazakh cuisine. Now, one could find Kazakh household dishes that are influenced by Arabian, Tatar, Uzbek, Uygur, Korean, and Russian culture.

Modern-Day Kazakh Cuisine

The cultural, political, and geographical ambiguity of Central Asia brought about by the Soviet Rule had irreversibly affected Kazakh cuisine. Therefore, Kazakh cuisine is difficult to distinguish from its neighbors; rather than any dish being “fully” Kazakh, it is more that there are common meals among the Central Asian region that have adjusted to the ingredients most available in the Kazakh region. Thus, it could be understood that the dishes that are mentioned below are rather Kazakh “versions” of the dish, rather than a uniquely Kazakh dish.

Based on my experience, Beshbarmak is almost always the first dish brought up in a discussion of Kazakh cuisine. Beshbarmak is a classic Kazakh dish with wide noodles, onions, meat (horse, mutton, or beef), and herbs. Beshbarmak means Five Fingers because it is traditionally eaten with your hands. Plov is originally an Uzbek dish, but the Kazakh version is made with rice, carrot, onion rings, and pieces of fried mutton. Lagman is a Uygur dish with long boiled noodles with fried meat and vegetables, and it can be served either in a soup or not (156). Just from this small range of dishes, one could observe that dishes that are commonly eaten in Kazakhstan come from a variety of cultural backgrounds.

It is difficult to determine the staple food in Kazakhstan. Many also had difficulty answering this question in the interviews. After some thought, some would bring up meat, others would point to bread or milk,—to sum up, there was no general consensus. Historically, milk and other dairy products have played a significant calorific role in the diet of nomadic people due to its portability. Thus, the practice of consuming dairy products has translated into the current Kazakh lifestyle. In supermarkets, one could find a variety of different dairy products from regular milk, kefir, sour cream, and more. Even in the category of milk, one could find milk from cows, camels, donkeys, and goats. Milk is generally served in its natural form in tea or as a fermented form and is served first along with baursak (traditional Kazakh fried bread) in a Kazakh feast (Tredinnick and Dagmar 2018, 152). The familiarity of dairy products is one of the reasons why sushi and pizza have gained the unwavering popularity that it holds in Kazakhstan today, which will be discussed further in a later section.

However, in current households, it could be argued that bread has become a staple food that is an “addition to all dishes” as stated by Sofya Detkina, a sixteen-year-old Kazakh girl of Russian descent. During the Soviet rule, Soviet-style “Poor man’s bread” became a key component to Kazakh households. There are also geographical reasons for the significant presence of bread in Kazakhstan. The Soviet economy was largely based on agriculture and in Northern Kazakhstan, the soil and climate proved to be ideal for grain culture. Still today, one could find a variety of different types of grains and flour in supermarkets and bazaars as well as a large selection of bread from the traditional flatbreads (taba nan, dandy nan, tandyr nan, etc.), to more Western bread such as danishes (Tredinnick and Dagmar 2018, 157). Countries around the world, including Japan, are beginning to show their interest in Kazakhstan’s agricultural business, especially in wheat and grain production. In 2014, Toyota Tsusho Corporation had begun to invest in Koktem EA, a Kazakh agricultural corporation, and has also recognized Kazakhstan to be a “priority emerging country” (Toyota Tsusho 2014).

- Japan and Kazakh Relations

Japan and Kazakhstan’s official diplomatic dialogue began in May 1992, soon after Kazakhstan gained independence in December of 1991. Bilateral relations began after Michio Watanabe (former Japanese Minister of Foreign Affairs) visited Kazakhstan, and two years later, former President Nur-Sultan Nazarbayev went to Japan and signed a joint statement. However, cultural exchange between the two countries began long before in the middle of II century B.C, with Japanese porcelain bowls having been found in excavations made nearby Almaty (Baipakov 2003, 14). Although there may not have been direct trade between the two groups, it is still significant to understand that Japanese goods made their way to modern-day Kazakhstan through the Silk Road[1].

As if to reinvoke the intercultural exchange of the past, the Japanese government launched a diplomatic initiative calling for the re-establishment of the Silk Road. The Silk Road Diplomacy focused on fostering intraregional cooperation between Central Asian countries and Japan in aspects of the economy and diplomacy. There was great emphasis on natural resource development in the Central Asia area, as Japan, among many other global powers, has an interest in Kazakh uranium and other raw materials.

The Kazakh (and overall Central Asian) perception of Japan is positive in contrast to views shared by many East Asian countries (Dadabaev 2019, 2). A poll by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs demonstrated that 59 percent of Kazakh respondents considered the Kazakh-Japan relations to be on good terms, and a similar result was also observed in the AsiaBarometer survey conducted by the University of Tokyo (2). Timur Dadabaev (2019) from the University of Tsukuba in Japan, attributes such positive perceptions to the fact that there have never been imperial tensions between Central Asian countries and Japan. Instead of associating Japan with its imperialist history, Central Asia views Japan as a country that has withheld oppression by the West and has grown to become a part of it through “technological progress” while still retaining its traditional values (2). Such history appeals to the Turkic and Muslim communities in Kazakhstan who have been oppressed by the Soviet Union and more recently, the growing Chinese influence. Central Asia also views the people of Japan in a positive light, referring to them as polite people with “proper manners” (2).

The current Kazakhstan-Japan relations are seen to reflect images of Japan as a progressive technological society with a rich tradition and culture. For example, in July of 2010, the Kazakhstan-Japan Innovation Center (KJIC) was established in partnership with Kazakh National Agrarian University and Japanese corporations such as JEOL and Shimadzu (Kazakhstan-Japan Innovation Center). The center promotes joint international research in various fields of technology and provides application-based training for graduate and doctoral candidates (Kazakhstan-Japan Innovation Center). The Japanese Embassy in Kazakhstan also initiates the cultural exchange by organizing and taking part in events such as the Japanese Culture Day in Almaty, Hanabi Fest (similar to Comic-Con), among many others.

Central Asian countries, including Kazakhstan, are hopeful of Japanese investments as an alternative to China and Russia which are cautioned for due to past history of political and economic extortion (Lincoln 2015). However, Japanese corporations have yet to fully enter the Central Asian market. Despite Kazakhstan being the main source of imports and exports in the Central Asia area, the overall share of imports when compared to the global scale is rather insignificant (239). Lincoln (2015) points out two main factors for the weak Japanese influence in the region: supply reliability due to political uncertainty and Chinese influence in the region (253). Although the current Japanese corporation presence in Kazakhstan is weak, there is still potential for further investment, especially in energy and raw material trade.

- Trends in the “Glocalization” of Japanese Cuisine Around the World

When looking at the expansion of Japanese restaurants exclusively, whether a community has a significant Japanese food scene is centered around the presence of Japanese corporations and henceforth Japanese expatriates in the region seeking a taste of home. After restaurants are introduced to an area by Japanese corporate elites, these restaurants then become expanded to cater “to local elites and eventually to ordinary urbanites” (Farrer et al. 2019, 47). Most large Japanese companies are found in urban global finance and trade centers. However, in developing economies where Japanese companies are increasing their investments such as in Vietnam, Farrer et al. (2019) state that they are still in the process of increasing the number of Japanese companies and henceforth Japanese restaurant owners (47).

Following the introduction phase of Japanese restaurants, it is argued that next comes the “glocalization” and ethnic succession phase (47). Glocalization of sushi is said to have been introduced by Japanese chefs in Los Angeles who attempted to mitigate the “foreignness” of sushi by adjusting it to better suit the Western palate. Although there is debate as to when the California roll (crab, cucumber, and avocado) was invented, this innovation initiated the movement of restaurants distinguishing themselves through unique, localized sushi rolls. The Philadelphia roll (salmon, avocado, and cream cheese), Boston roll (avocado, shrimp, and cucumber), British Columbia roll (barbecued salmon skin and cucumber) are all examples of sushi rolls that did not originate from Japan but have now become global dishes. Ethnic succession in Japanese cuisine is the process of other ethnic groups (primarily of other East Asian ethnicities such as Koreans, Taiwanese, and Chinese) taking over Japanese restaurants or opening up their own.

However, this trend of “glocalization” and ethnic succession can only be achieved if there is a significant Japanese expatriate population in the region. In countries such as Kazakhstan where Japanese corporations have yet to establish a significant presence, it is hypothesized that the introduction and popularization of Japanese cuisine are primarily fueled by non-Japanese chefs, entrepreneurs, and consumers.

- Japanese Cuisine in Kazakhstan

As discussed previously, the Kazakh people generally have a positive image of Japan, and this extends across to Japanese cuisine as well. Especially in the younger generation, Japanese cuisine has increasingly become popularized due to the growing recognition of Japanese subcultures as well as the presence of social media enabling the connection of information and knowledge across the world.

An exact time in which Japanese cuisine entered Kazakhstan is not known. Daulet Bakhtiyar, a man in his mid-thirties married to a Japanese woman, said that the first time he encountered Japanese food in Kazakhstan was a sushi store from Russia in the early 2000s. Similarly, Gulshat Burkhanova, a woman in her early thirties, mentioned she only remembers there being about two sushi shops fifteen years ago. It is theorized that sushi rapidly grew in popularity in the last decade when new malls were built, and international companies began to further invest in the Kazakh market. This influx of different cultures is thought to have created room for a variety of international cuisines to become familiarized in the country. Thus, entrepreneurs who saw a business opportunity in starting Japanese cuisine in Kazakhstan increasingly began to open up restaurants or sell Japanese goods in supermarkets.

Now, there are four out of forty-eight restaurants in one of the largest malls in the country, the MEGA Alma-Ata shopping and entertainment center shopping center, which focus on serving Japanese cuisine (Sushi Master, Scarlet Sails, Yasuda Sushi, and Yakitoriya), in addition to a number of other restaurants that also have some Japanese dishes on their menu. The number of restaurants serving Japanese dishes demonstrates the extent to which Japanese cuisine has become accepted in Kazakh society.

Rather than the global trend that has been observed in many parts of the world such as the United States, Hong Kong, and London, the popularization of Japanese cuisine in Kazakhstan is fueled by non-Japanese chefs, entrepreneurs, and customers. This expansion of Japanese cuisine by non-Japanese ethnic networks is postulated to be due to the globalization of the American-style sushi and the perception of Japanese cuisine as being healthy and trendy.

In terms of flavor, the general consensus obtained from the interviews was that Japanese food was mild and light. Compared to food the Kazakh people are used to eating on a daily basis, Japanese food seemed to lack taste for some individuals. Sofya Detkina stated that she feels Japanese food is “rather bland and too mild” for her liking. However, she also pointed out that this probably made Japanese cuisine healthier than other cuisines, or at least Kazakh cuisine which uses a lot of salt and oil. Two women in their early thirties also both expressed that Japanese cuisine was very popular for health-conscious people. They brought up dishes such as miso soup, sushi, and seaweed salad that they would often find advertised as a “healthy” option on menus when dining out. In addition, they mentioned that going out to eat Japanese food was quite popular and trendy, and hence they often see their friends posting pictures on their social media.

I also observed a similar perception of Japanese food as “trendy” during the short period of time I spent in an International school in Kazakhstan. Although an International school, approximately half of my class were Kazakh nationals. In conversations with my peers, I would often hear them mention that they had sushi for dinner last night or see them post pictures on their social media when they ate or even made sushi. Social media may be one indicator that demonstrates the perception of Japanese food as “trendy” in the younger generation of Kazakhstan.

- Sushi in Kazakhstan

Sushi was almost always the first word brought up when interviewees were asked for a word that immediately came to their mind when thinking of Japanese cuisine. Like in many countries around the world, sushi has gained widespread popularity in Kazakhstan. One reason for sushi’s popularity in Kazakhstan is hypothesized to be customization. Consumers are able to customize their sushi by altering the intensity of the taste based on how much soy sauce or other sauces are put on each piece of sushi. As discussed above, many of the interviewees expressed that their image of Japanese food was mild and rather bland at times. Therefore, if one is able to control the amount of soy sauce, wasabi, or some other form of condiment they put on each piece of sushi, there is room for individualization before consumption.

Customization can also occur in the process of creating sushi, as demonstrated through the creative compositions and designs that transform sushi in a multitude of ways. First, originality can be demonstrated through whether the seaweed is wrapped around the outside, the inside, or if it is even present. If there is no seaweed, the sushi may be wrapped around or topped with another ingredient; avocado, mango, egg, sesame seeds, flying fish roe (tobiko), pickled radish (taku-an) or smeared with tempura batter and fried. Second, the sauce that is put on sushi is also variable. While some forms of sushi will be served plain with the intent that individuals apply soy sauce before consuming, some sushi in Kazakhstan can be served with other sauces: teriyaki sauce, mayonnaise, thousand island sauce, additional cream cheese, are just examples from the many types of sauces that can be found applied to sushi. The variation could also come in terms of the size, presentation, or what other dishes the sushi is served along. The various customizations enable restaurants to distinguish themselves from their rivals by serving unique creations on their menu.

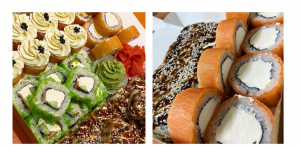

As dairy products are familiar to the Kazakh palate, the most popular sushi generally has some form of cheese incorporated. “Yeah, American style sushi is more popular, especially those with a lot of cheese, cream cheese, or mayonnaise. Most people order Philadelphia,” says Dana Bulzhanova. Another reason for the predominance of dairy products in sushi found in Kazakhstan is economic factors. As Kazakhstan is a country surrounded by land, all seafood must be imported. Among the imported seafood, those that are at a safe level to be consumed raw are in small numbers, and therefore, seafood is still predominantly a rare luxury. To compensate for the lack of seafood, many sushi chains will provide sushi that includes cream cheese as the primary component along with other cheaper alternatives such as cucumbers, imitation crab meat, and chicken (fig. 5.1). As dairy products are made locally, they could be found at relatively affordable price points. Therefore, although sushi is becoming widespread, one of the primary reasons why American-style sushi is more popularized may have to do with the economic background.

However, non-Japanese ethnic businesses have portrayed American-style sushi to be authentic to Japan, creating a wide misconception. Despite the disparity between Japanese cuisine found in Japan compared to Kazakhstan, many restaurants will capitalize on Japanese culture in order to attract more customers by presenting an air of exoticism. Although these dishes may be presented as being “exotic” food, the reality is that this exoticism is a pretense; the “foreignness” is limited within a border so that the dish is just exotic enough to stimulate the intrigue of customers, but still be familiar. This is another reason why American-style sushi is more popular and common; while being presented as a foreign dish, it incorporates additions that put the sushi within the border of familiarity.

Sushi and Orientalism

Almost all Japanese restaurants in Kazakhstan are not owned by Japanese people, but by non-Japanese entrepreneurs who view the emerging popularity of Japanese cuisine as an opportunity to succeed in the growing Kazakh market. Therefore, the distinction between the various Asian cultures is not prioritized and most times unrecognized in the creation of Asian restaurants. Many stores will conflate Japanese culture with other Asian cultures. Therefore, stores that present themselves as Japanese restaurants will essentially be similar in their overall presentation and the variety of dishes offered to other Asian restaurants. As the target audience of such restaurants is not Japanese people but the local Kazakhs, their primary purpose is to sell an exotic atmosphere to customers, not authenticity.

Rather than seeking adherence to Japanese culture in Japan, most restaurants have curated the image of their restaurant through stereotypes and imagination of Japanese and East Asian culture in general. This is first made obvious in the naming of the restaurant itself. Restaurant names such as “Ziyama Sushi,” and “Dakeshi Sushi and Pizza” may all sound as if they were Japanese to people who do not know the language when in reality, they are merely words that sound Japanese.

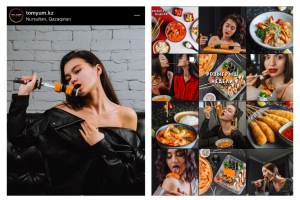

Social media advertisements of sushi stores are used to attract the younger generation in Kazakhstan, the primary audience of Japanese cuisine. Social media posts function to visually portray an image of East Asia associated with orientalism and at times, eroticism. Heldke (2012) suggests that by associating food with the sexual imagery of women, the emphasis of the exoticism of the food is increased (183). Such a tactic is adopted by a restaurant called “Tom Yum House”, which identifies itself as a sushi restaurant that serves other Asian fusion dishes such as wok, Tom Yum, as well as pizza. Their social media post below (fig. 5.2) is one such example of the utilization of orientalism and eroticism; in the image, a woman is seductively eating sushi rolls that have been punctured through an imitation katana (knife). Other examples include a woman eating a piece of nigiri sushi that is placed on her bare shoulder or two women pretending to eat noodles mouth to mouth.

Representation of Japan through orientalism and sexual inferences has been perpetuated in various areas around the world, with Japan in certain ways using this portrayal to strategically mark themselves in the Western market. Such perceptions of Japanese culture have also been shared in Kazakhstan, and hence utilized in social media advertisements as a business tactic to lure in more customers.

As social media is a way to communicate the atmosphere of the restaurant through images and text, it is only natural that restaurants themselves also present oriental stereotypes. An example of a store is “Sushi Master” which is located in the food court in MEGA Alma-Ata and MEGA Silk Way shopping and entertainment center, the largest malls in the country. The image below is the interior of the store; there is a large mural of a shadow of a samurai-like figure and an incoming wave depicted inside a red circle, and the name and logo of the store reflect the stereotypical image of an East Asian master (fig. 5.3).

Why oriental stereotypes are implemented is theorized to be due to the lack of information and knowledge of Japanese culture. Generally, facilitating the communication of undistorted knowledge of Japanese culture are Japanese ethnic groups in the region. However, due to the small Japanese population in Kazakhstan, there have not been many prominent opportunities for cultural exchange between the two countries. Thus, although there is increasing interest in Japanese culture including Japanese cuisine, the perception of Japan that is being relayed by non-Japanese groups are rather exaggerations that are built up upon oriental and exotic imaginations of Japan. For consumers who have not had prior exposure to Japanese culture, it is only natural that they come to believe images portrayed by Non-Japanese ethnic businesses are authentic. It is uncertain as to whether non-Japanese entrepreneurs who are the main perpetrators of orientalism are aware of the stereotypes they portray, or whether it is even a point of concern. It may be that cultural appropriation is an inevitable consequence of culinary mobility where there is a lack of access to Japanese culture relayed by ethnic Japanese networks.

Sushi and Pizza: A Uniquely Perfect Combination?

The combination of sushi and pizza is a unique pairing that has become rooted in Kazakhstan. The underlying reason for the popularity of the sushi and pizza combination is hypothesized to be the individual popularity of each dish. Although originating from distant countries and being starkly different in their composition, pizza and sushi share similarities in their malleability to become customized. Basic pizza and sushi are both rather simple and predictable in terms of their ingredients and taste; pizza will generally have a piece of dough with a sauce topped with cheese, whereas sushi will have nori (seaweed), rice, and generally fish. These basic forms are then able to be customized and henceforth adapt to different local preferences. In addition, both pizza and sushi (as most contain cream cheese) in Kazakhstan contain dairy products which are a familiar ingredient to local Kazakhs. These qualities have bolstered pizza and sushi to popularity in Kazakhstan, such that both dishes can be found on menus not restricted to Italian or Japanese restaurants, but also in restaurants from Uzbek, Georgian, to Korean. However, despite the popularity of pizza and sushi in many other countries, a sushi and pizza combination is not commonly established. Why is it that in Kazakhstan, the sushi and pizza combination has become a common model?

There were various speculations as to how the sushi and pizza combination came to be that was brought up in interviews. Daulet Bakhtiyar theorizes that this combination began when a chain company based in Russia opened up two separate restaurant chains in Kazakhstan, one that specialized in pizza, and the other sushi. These shops expanded across Kazakhstan and grew in popularity, but as both chains were owned by the same parent company, these shops eventually combined to become one brand. Due to this brand’s success, this combination became a business model for quick success that became grounded in Kazakhstan and imitated by coming restaurants.

Additionally, Gulshat Burkhanova, speculates that sushi rolls and pizza play a similar role as modest luxuries. In addition, she stated, while pizza may be rather greasy and quite filling to the stomach, sushi seems “healthier” in contrast, creating a balance. Sofya Detkina also voiced a similar opinion, stating that the use of different carbohydrates complements each other rather than clash. Although pizza and sushi may seem to contrast each other in their position on the table as the main dish, from another perspective, the two perhaps make an unexpected match. The combination of two seemingly disparate dishes may be an idea that non-Japanese entrepreneurs have been able to recognize and implement by prioritizing local popularity and profit over authenticity.

Although the pizza and sushi combination could be ordered to be eaten individually or within the immediate family, it is more commonly ordered at larger gatherings as part of a feast. Thus, delivery services will often provide a discounted price for the sushi and pizza party-set. Advertisements for such services are regularly found on social media advertisements (fig. 5.5). In addition, it may be that the sushi and pizza combination also allows for larger groups that may have different preferences to have a variety of choices to choose from in terms of whether they would like sushi or pizza, and even among each, what type they would like. The climate and geography are another reason for the popularity of delivery services and hence the pizza and sushi combination. Especially in the capital Nur-Sultan where the average temperature in the winter is approximately -20 degrees Celsius, for one to go anywhere, they will require a car. Thus, delivery is a popular convenient option for families who live in urban areas and are able to afford it.

- Café Momo: Ethnic Japanese Businesses and their Role

While sections prior focused on non-Japanese entrepreneurs, chefs, and customers as facilitators of the expansion of Japanese cuisine, this section will discuss an exception. It is argued that once the target audience of a restaurant includes people who have been predisposed to Japanese cuisine, an expectation of authenticity is created. Therefore, restaurant owners are posed to find a compromise between complying with local tastes and managing authenticity.

One of the only Japanese restaurants in Nur-Sultan that cater to both Japanese expatriates and local Kazakh customers is Café Momo, a restaurant Café owned by a Japanese chef (fig. 6.1, 6.2). A former baker in Japan and in the UAE, Daisuke Kishigami moved to Kazakhstan when he married his Kazakh wife. As there were very few to no Japanese chefs in Kazakhstan, he thought that it would be a perfect opportunity to open his own business in Kazakhstan. Originally wanting to open a bakery in either Nur-Sultan or Almaty, he researched the market in those areas. However, he came to the conclusion that it would be difficult to start a successful business with bread due to the lack of recognition and interest in Japanese bread. Instead, he opened up a Japanese Café serving home-style Japanese cuisine at affordable prices to distinguish his business from other Japanese restaurants and pique people’s interests.

The location of the restaurant is an integral part of his business. Although the primary audience is local Kazakh people, Café Momo also targets foreign expatriates, including Japanese expatriates. Located in the middle of an apartment complex where most foreign expatriate families live, he is able to attract customers who may have already been exposed to Japanese food in other countries. Some Japanese customers (most of who are single men) have expressed that they would go to the restaurant at least three times a week, some even going every day. For Japanese expatriates who want a taste of their homeland without putting in the effort to cook their own meal, Café Momo is a perfect oasis. However, the primary audience who come to Café Momo is Kazakh customers, most of who were already interested in Japanese culture. Therefore, the restaurant presents Japanese culture through an array of forms such as posters of scenic Japanese views, shelves full of Japanese books and goods, as well as through the Japanese music playing in the background.

The diversity in customers is demonstrated through a variety of factors that are taken into account. Firstly, menus are offered in three languages, Russian, English, and Japanese to accommodate the local Kazakh, foreign expatriate, and Japanese customers who visit the restaurant. In addition, the restaurant offers a range of meat options to cater to people of various religious backgrounds. As shown in the English menu (fig. 6.3), for each dish, one could choose what type of meat they would like out of chicken, pork, or beef. For example, Katsu is available as either chicken or pork, as well as the curry having a chicken or beef option. While a typical teishoku-ya (diner) in Japan may not provide the option to choose what type of meat gets used, in Kazakhstan where the majority are Muslim with a spectrum in terms of adherence, this flexibility may perhaps be another factor contributing to the restaurant’s diverse audience.

When asked whether any special effort is made to better cater to the Kazakh palate, Kishigami stated that he does not do anything in particular with the flavor. However, he is observant of his customers’ words and actions and takes them into consideration when altering the composition of a dish or adding new dishes to the menu. For example, he mentioned that a common request is to add more sauce on dishes such as Hambaag (minced beef steak), Katsu (fried cutlet), and Korokke (fried mashed potato). “I think Kazakh people are more used to having a thick, rather salty taste. That’s why I provide a sauce in a squeeze bottle so each person can alter the amount of sauce to their liking,” Kishigami explains.

However, telling of the ambivalence between authenticity and adhering to local expectations and tastes is the sushi menu (fig. 6.1, bottom right). On the menu are basic sushi rolls such as tekka maki (tuna roll) and kappa maki (cucumber roll), regional sushi rolls such as saba-zushi (mackerel sushi), as well as American-style sushi rolls like Philadelphia rolls and California rolls. Kishigami mentioned that American-style sushi rolls are the most popular in the restaurant, although they may not be authentic to Japan. “I think people in Kazakhstan are not as adventurous in their food choices. Because they know what Philadelphia rolls taste like from other sushi places, they also tend to choose it here.” Therefore, to learn how to make sushi, Kishigami invited a sushi chef that had been working in Europe for over fifteen years who was familiar with making sushi that would be better accepted by the local people. However, Kishisgami also adheres to people who have been predisposed to authentic sushi by providing sushi rolls that are commonly found in Japan, such as futo-maki (large sushi with a variety of ingredients inside), tekka-maki, unakyu-maki (eel and cucumber roll), etc.

When asked why there is no nigiri-zushi that is generally evoked when thinking of sushi in Japan, Kishigami stated that he simply did not have the skill and that the quality and variety of fish available in Kazakhstan enacted a limit to what he could offer at an affordable price range. Thus, another factor that plays into fulfilling authenticity is practicality; for the cost, time, and skill required to provide authenticity, the actual benefit may not be on par in environments with a small ethnic Japanese population.

- Japanese Goods in Supermarkets

Non-Japanese ethnic networks are crucial in expanding Japanese cuisine in Kazakhstan, even in the realm of home cooking. In emerging urban centers such as Nur-Sultan with a small population of Japanese expatriates, non-Japanese companies who provide low-cost goods and services are the main facilitators of Japanese cuisine. However, the provision of low-priced goods may come at a cost of quality, cultural appropriation, and a divergence from the original Japanese cuisine.

Similar to the perception of Japanese culture demonstrated in restaurants in Kazakhstan, Japanese goods and ingredients sold in local supermarkets evoke sensations of orientalism. These “Japanese” goods are actually not from Japanese brands but are from Russian, Kazakh, and Chinese companies. The three main brands that commonly sell Japanese goods in local supermarkets are Mayumi, Sen Soy, and Yum Yum. Sen Soy is owned by a Russian parent company SOSTRA, and Yum Yum is owned by another Russian company Virtex Food. Both Sen Soy and Yum Yum sell their products to neighboring countries of Russia, such as Armenia, Belarus, Azerbaijan, Ukraine, the Baltic States, as well as Kazakhstan. Mayumi is supplied by Zhongshan Weifeng foodstuffs Co. Ltd, a Chinese company specializing in Asian food products.

The three main categories of Japanese goods sold by these brands are noodles, ready-made sauces, and ingredients to make sushi. The types of noodles that are generally found are soba, udon, and sōmen, but vermicelli is also sold as “Japanese food” at times as Japanese and other East Asian cultures get conflated. Teriyaki sauce is the most common sauce sold, but other ready-made sauces such as yakitori sauce and unagi sauce could also be found. The basic ingredients and material required to make sushi such as rice vinegar, nori (seaweed), “sushi rice,” soy sauce, wasabi, and a sushi mat are also commonly found.

As these companies do not target an audience that is familiar with authentic tastes, the companies will feign authenticity through their packaging. When one takes a close look, the recipes written on the back of each product are often far from what the dish may be in the original culture. For example, the brand Sen Soy wrongly states that Yakisoba (fried noodles) is made with “traditional Soba buckwheat noodles,” when in fact, they are usually made from Chinese wheat flour noodles (Sen Soy).

There are many other ways the brand Sen Soy incorrectly relays Japanese cuisine. Sen Soy sells four types of noodles: udon, soba, sōmen, and egg noodles (fig. 7.1). The packaging of these noodles all has a mountain evoking Mount Fuji backed by a red sun with the words “Japanese Cuisine” printed in Russian (Японская кухня) to try and invoke “authenticity”. While the former three noodles, udon, soba, and sōmen are Japanese dishes, egg noodles are not Japanese cuisine as the packaging claims it to be. In addition, the kanji (Chinese characters) written for udon is not in Japanese. While the packaging writes udon as鳥冬, the proper kanji for udon in Japan is 饂飩. The kanji depicted on the packaging 鳥冬 is the Chinese for wu dong which phonetically sounds similar to udon and therefore is not Japanese. The various erroneous ways the brand communicated knowledge of Japanese cuisine indicates that the brand prioritizes the feeling of exoticism rather than supplying authentic Japanese products.

European brands that sell Japanese goods are found in Kazakhstan, but in limited varieties in supermarkets frequented by foreign expatriates which have a wider selection of imported goods. These goods are more expensive than the local Russian, Kazakh, and Chinese brands. However, Japanese goods from Japanese brands could barely be found in the various supermarkets that I went to, except for Kikkoman soy sauce imported from Russia and Nissin Cup Noodles imported from the United States. The Kikkoman soy sauce was found in most local supermarkets in the Nur-Sultan area, however, Nissin Cup Noodles was only found once during a visit to a supermarket frequented by foreign expatriates.

The price disparity between the different brands from the various countries is most evidently recognizable when comparing prices of soy sauce from the various brands (fig. 7.3). All bottles of soy sauce are 150ml. The local Mayumi brand is 810 KZT, the Clearspring brand from the UK is 5915 KZT, and the Kikkoman brand 2135 KZT. For the average local Kazakh, the Clearspring and Kikkoman soy sauce is a luxury. The Clearspring brand is imported from the UK as well as it being organic, which is most likely why it is more than double the price of the Kikkoman brand which although is a Japanese brand, is manufactured and imported from Russia and therefore cheaper.

Korean goods are more commonly found in many supermarkets. Due to the history of mass immigration, there is a large ethnic Korean community in Kazakhstan. Therefore, there are many Korean companies in Kazakhstan and thus a few Korean grocery stores in the Nur-Sultan area. On the contrary, the Japanese population in Kazakhstan is extremely small, and Japanese corporations have yet to find a definitive incentive to invest in the Kazakh market. Although there are diplomatic discussions to recultivate the Silk Road, this is limited to energy and raw materials exported to Japan, rather than importing goods from Japan. As there is no direct trade route that connects Japanese food companies to export goods into Kazakhstan, there are almost no Japanese food products that are directly imported from Japan.

Currently, for Japanese products to enter the Kazakh market, they will first need to go through another country before coming to Kazakhstan. This creates additional costs, making the products even more expensive. Henceforth, Nissin Cup Noodles which can be found at approximately 208 yen in Japan are sold in Kazakhstan at around 960 KZT (235 yen). To put it into perspective, local instant cup noodles could be found at 165 KZT. The average monthly income in Kazakhstan (211033 KZT, approximately 51899.58 yen as of December 2020) is approximately six times lower than the average Japanese (302410.00 yen) (Agency of Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan 2020, Ministry of Health 2020). The difference in average income between Kazakhstan and Japan may be another reason that disincentivizes Japanese corporations from entering the Kazakh market.

- Future of Japanese Cuisine in Kazakhstan

The fact that a variety of different ingredients used to make Japanese cuisine are sold in numerous supermarkets tells us that interest in Japanese cuisine is not limited to a restaurant setting. For proof, non-Japanese entrepreneurs have capitalized on the lack of Japanese corporations in Kazakhstan and have created successful businesses by targeting local Kazakh interests.

However, when interviewees were asked whether Japanese cuisine will potentially enter the daily household menu, all indefinitely agreed that this chance would be very slim. One of the main reasons posed was the small number of Japanese nationals that currently live in Kazakhstan. Historically, how cuisine from different cultures entered the Kazakh households was from mass immigration. For example, Korean immigrants who were exiled to Kazakhstan created the “Kazakh-style Korean Salad” which is said to have originated from using carrots instead of Chinese cabbage to make kimchi, as ingredients used back in Korea were not found in Kazakhstan. Other culinary cultures that have been engrained in Kazakhstan are the sauerkrat by the Germans, borscht from Ukraine, and most significantly the presence of bread in Kazakh households introduced by the Russians. As of 2019, there were a total of 171 Japanese residents in Kazakhstan and it can be assumed that numbers have decreased with the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak. For a Japanese culinary dish to make a name on the Kazakh household menu, a larger presence of the Japanese ethnic community may need to be established.

However, from another perspective, the localization of sushi despite the small ethnic Japanese population is a clear statement of the tenacious popularity of Japanese cuisine, despite the various limitations in terms of availability of ingredients and lack of direct knowledge from ethnic Japanese groups. The wide recognition of Japanese cuisine in Kazakhstan has clearly proved the essentiality of non-Japanese ethnic networks in the expansion of culture. While this mobility of Japanese cuisine may not always be genuine to what is found in Japan, halting an already emerging wave is near impossible. Instead, Japan should make various efforts to promote opportunities for cultural exchange that provide the knowledge and resources to these areas in order to allow for even better appreciation of Japanese cuisine.

Conclusion

This paper on the culinary mobility of Japanese cuisine in Kazakhstan argued that the expansion of Japanese cuisine in Kazakhstan was facilitated by non-Japanese ethnic networks in areas with a small ethnic Japanese population. Although historically the dispersion of cultural goods had been promoted by diaspora, the proliferation of Japanese cuisine in Kazakhstan through non-Japanese ethnic groups demonstrates the limitations of such models. While this paper solely focused on the mobility of cuisine, broader implications of how cultural goods may be portrayed and transmitted in another culture could also be understood.

However, it must be acknowledged that this paper only studied the expansion of cultural goods in urban areas of Kazakhstan, specifically Nur-Sultan, and did not include rural regions. In addition, without further research in other countries with a small ethnic Japanese population, it could not be stated with certainty that this theorized model will hold true. Therefore, future research should be conducted in more countries with similar characteristics in terms of ethnic Japanese presence and access to resources, as well as in more rural environments to evaluate the validity of the argument made in this paper.

References

Baipakov, Karl. “The Great Silk Road and Kazakhstan.” Kazakhstan and Contemporary World 3, no. 6 (2003): 14–18.

Central Intelligence Agency. “The World Factbook: Kazakhstan.” Central Intelligence Agency, February 1, 2018. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/kz.html.

Dadabaev, Timur. “Central Asia: Japan’s New ‘Old’ Frontier. Report. East-West Center, 2019. Accessed November 3, 2020. doi:10.2307/resrep21456.

Farrer, James, Christian Hess, Mônica R. De Carvalho, Chuanfei Wang, and David Wank. “Japanese Culinary Mobilities.” Routledge Handbook of Food in Asia, 2019, 39–57. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315617916-4.

Heldke, Lisa. “Let’s Cook Thai: Recipes for Colonialism.” In Food and Culture: a Reader – 3rd. Ed., ed. Carole Counihan and Penny Van Esterik, 175–93. New York: Routledge, 2012.

“Japan Average Monthly Wages 1970-2020 Data: 2021-2022 Forecast: Historical: Chart.” Japan Average Monthly Wages | 1970-2020 Data | 2021-2022 Forecast | Historical | Chart. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Accessed December 21, 2020. https://tradingeconomics.com/japan/wages.

“Japan-Kazakhstan Relations (Basic Data).” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, November 5, 2020. https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/europe/kazakhstan/data.html.

“Kazakhstan Average Monthly Wages 2000-2020 Data: 2021-2022 Forecast: Historical.” Kazakhstan Average Monthly Wages | 2000-2020 Data | 2021-2022 Forecast | Historical. Agency of Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Accessed December 21, 2020. https://tradingeconomics.com/kazakhstan/wages.

“Kazakhstan-Japan Innovation Center.” КазНАИУ – Казахский национальный аграрный исследовательский университет. Accessed December 22, 2020. https://www.kaznau.kz/page/japan_center/?lang=en.

Lincoln, Edward J. “Japan and Korea in Central Asia: Economic Observations.” In China, The United States, and the Future of Central Asia: U.S.-China Relations, Volume I, edited by Denoon David B. H., by Jenish Nazgul, Laruelle Marlene, Kuchins Andrew, Sharan Shalini, Li Xin, Xin Daleng, Xing Guangcheng, Khamidov Alisher, Peyrouse Sebastien, Lincoln Edward J., Sachdeva Gulshan, Walker Joshua W., Pomfret Richard, Pan Guang, and Kissane Carolyn, 237-61. NYU Press, 2015. Accessed November 15, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt15vt94p.12.

Smith, David Roger, Edward Allworth, Gavin R.G. Hambly, and Denis Sinor. “Kazakhstan.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., December 17, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/place/Kazakhstan.

SOSTRA. “Dear Friends!” About. Accessed December 21, 2020. https://en.sostra.ru/about/.

Sultanov, B. K. Kazakhstan Today. Almaty: The Kazakhstan Institute for Strategic Studies under the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2010.

“Sushi Master.” ТРЦ MEGA – сеть торгово-развлекательных центров в Казахстане. Accessed December 22, 2020. http://mega.kz/mega.silkway/brands/shop/sushi-master/.

“Toyota Tsusho Invests in Koktem EA, an Agricultural Corporation-First Entry into the Country’s Agricultural Industry-.” Toyota Tsusho, July 3, 2014. https://www.toyota-tsusho.com/english/press/detail/140703_002657.html.

Tredinnick, Jeremy, and Dagmar Schreiber. Kazakhstan: Nomadic Routes from Caspian to Altai. Hong Kong: Odyssey Books & Maps, 2018.

Yemelianova, Galina M. “Muslims of Central Asia before the Russian Conquest.” In Muslims of Central Asia: An Introduction, 11-31. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019. Accessed November 15, 2020. doi:10.3366/j.ctvxcrxf6.9.

“Virtex Food.” История – VIRTEX FOOD. Accessed December 21, 2020. https://virtex-food.ru/company/history.

[1] The Silk Road was the largest network of trade routes in the ancient world. Stretching across the Eurasian continent, it indirectly connected Europe to imperial powers of East and Southwest Asia through mercantile centers in Central Asia. Along the Silk Road, not only did tangible goods get traded, but a myriad of cultural practices, religions, languages, and ideas were exchanged and spread throughout the world over thousands of years. This commerce network extended through modern-day Kazakhstan, and it is known that nomads themselves were significantly involved in trade, facilitating the transport of caravans between significant trading centers.