Introduction & Methodology: Buddhist Triptych

It is undeniable that part of the appeal of Buddhist cuisine today is its appeal to authenticity. The popularity of Buddhist monk- or nun-chefs, as well as Buddhist-themed cooking shows, speaks to this. In one sense, Buddhist cooking is indeed quite “authentic” to East Asia. Buddhist food, cooking styles, and philosophies about cooking have had immense impacts on East Asian cuisine since the 3rd century CE. In another way, however, Buddhist cuisine’s long history in East Asia means that it has endlessly been altered and appropriated for new purposes and contexts. While some traditional Buddhist dishes are still made in the way they have been for hundreds of years, many elements originally part of Buddhist cuisine, such as meat substitutes, have broken off and proliferated as non-Buddhist dishes, while other traditional dishes continue to be adapted for modern contexts. What is “authentic Buddhist cuisine,” then, when tradition is constantly in translation?

To explore this question, I picked two dishes linked to Buddhist cuisine, and one that is a bit of a pickle. The first was a dish from Japanese shōjin ryōri, or traditional monastic cuisine. The specific dish I chose was kenchinjiru, named after a Zen Buddhist temple in Kamakura, Kencho-ji.[1] Elements of interest to me were the fact that the recipe called for vegetarian dashi made using konbu and dried mushrooms, and the fact that it used a plethora of vegetables familiar to me only through Yamato Ama-dera Shōjin Nikki, a Japanese TV show about a small group of nuns and the delightful food they make. The dish shows Buddhist flavor innovation in the absence of fish products to season the soup, as well as the key role of vegetables.

The second dish I chose was not a Buddhist dish at all, but one traditional to Hong Kong–hongshao kao fu, which the recipe author calls “red braised wheat gluten kao fu.” Despite not being a Buddhist dish, it is vegetarian, and uses the Chinese meat substitute mian jin, also known as kao fu when boiled or steamed.[2] This dish reflects Buddhist influence on broader Chinese food culture, especially the role of mock meat. Rachel Laudan, in Cuisine and Empire: Cooking in World History, identifies mock meat made from tofu or wheat gluten as one of the two greatest contributions made to Buddhist food culture by the Chinese, the other being tea.[3] Apparently, it was an innovation that stuck. The anonymous author of the recipe blog The Hong Kong Cookery writes of hongshao kao fu, “just because it’s vegetarian fare, don’t expect the Chinese to give up their daily meat intake!”[4]

The final dish is a curious Western creation known as the “Buddha Bowl.” Essentially a recipe-less fad concept, it features some sort of grain, a plant protein, and vegetables (steamed, raw, pickled, roasted, you name it), and is generally vegan. The dish reflects an intriguing distortion of Buddhist cuisine, or rather, the idea of it. Bon Appetit writer Rachel Paley points out that Buddha bowls do not “have much to do with Buddha, or anything religious,” but she is somewhat missing the point.[5] After all, neither does hongshao kao fu. The draw of the Buddha bowl is more so the ideal of the exotic and the dream of Buddhist “healthiness,” rather than spirituality. Ultimately, it represents a complete departure from Buddhist cuisine, as well as the power of perceived authenticity.

Findings: The “Meat” of the Matter

For the mian jin and kao fu, I used recipes from the aforementioned anonymous creator of The Hong Kong Cookery blog.[6] For the kenchinjiru, I chose a recipe from the website Just One Cookbook by Namiko Hirasawa Chen.[7] Lastly, for the Buddha Bowl, I used ideas from several recipes, most of which were collections of suggestions more than anything else.

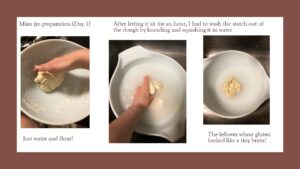

My journey began with the preparation for the vegetarian dashi. The konbu had to soak overnight, and I enjoyed watching it unfurl as it gradually rehydrated. I also prepped the dough for the mian jin. It consisted of only water and flour, kneaded to develop the gluten, then rested to relax the gluten. After the dough had rested, I had to knead and squish it in water to get rid of the starch, essentially “washing” the dough. The process took me around 20 minutes. I had never interacted with dough in this way before. I usually use dough to make pastries, so I am accustomed to being very gentle with it. This was a welcome change of pace.

My journey began with the preparation for the vegetarian dashi. The konbu had to soak overnight, and I enjoyed watching it unfurl as it gradually rehydrated. I also prepped the dough for the mian jin. It consisted of only water and flour, kneaded to develop the gluten, then rested to relax the gluten. After the dough had rested, I had to knead and squish it in water to get rid of the starch, essentially “washing” the dough. The process took me around 20 minutes. I had never interacted with dough in this way before. I usually use dough to make pastries, so I am accustomed to being very gentle with it. This was a welcome change of pace.

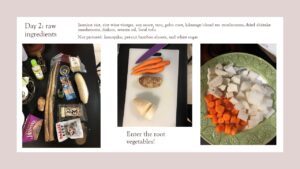

On the second day of cooking, I began with peeling and cutting the vegetables, as is my habit. I was fascinated with the texture of the taro, or satoimo, which I had never touched before. I then set about reconstituting the dried fungi–shiitake and kikurage, or “cloud ears” in Chinese (雲耳). I had almost missed the kikurage in the grocery store, since I was looking for the Chinese name. At the last moment, I remembered reading that the Japanese name was not “cloud ears,” but “tree ears,” 木耳. The similar, yet slightly differentiated names for this undeniably ear-shaped fungus reminded me of the close connections between Chinese and Japanese culture and thus cuisine.

Looking down at my work in progress, I realized how many parts of my meal were currently soaking in water–the konbu, shiitake, kikurage, even the gobo root was supposed to soak briefly. I was reminded of the emphasis on dried goods in Heian-period Kyoto, a historical echo that lived on in my many little bowls.[8] Once they were done soaking (to be quite honest, the shiitake stems were still as hard as rocks–I discarded them) I preserved the mushroom soaking water for later.

At last it was time for some heat. For the kenchinjiru, I sautéed the daikon, carrot, taro, gobo, shiitake, tofu, and konnyaku in sesame oil. Then I added the strained shiitake soaking water and the konbu dashi (which I had heated to the point of boiling, then removed the konbu). After bringing the soup to a boil, then back down to a simmer, I tended to it with the skimmer, removing the foam–a technique I had only ever seen in cooking or TV shows. At last, when the vegetables were tender (excluding the gobo, which I had cut into tragically large pieces that refused to soften), I turned off the heat and added a tiny bit of soy sauce. The soup steamed into my face as I tried each component, one by one. The taste and texture of each was delicate but distinct–the chewy, fishy konnyaku, the starchy taro, the earthy shiitake. All of them came together in a surprisingly complex way. Most importantly, of course, the kenchinjiru was beautiful to look at, each piece standing out in the semi-clear broth. It was a broth full of flavor, despite the lack of fish or alliums–a true shōjin success.

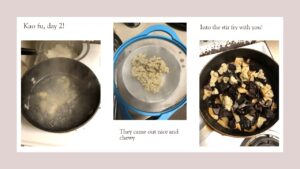

For the hongshao kao fu, I quickly boiled the mian jin, waiting for them to come to the surface like dumplings or my mother’s pierogi. Then I sautéed the bamboo shoots (I couldn’t find them fresh, only pre-packaged), kao fu, shiitake, and cloud ears in sesame oil, which was not the oil the recipe called for, but I decided it couldn’t hurt. I then simmered the ingredients in soy sauce, rice wine, mushroom soaking liquid, and a tiny bit of sugar for half an hour. The resulting kao fu were delightfully chewy, as promised, with a complex texture that held in flavor and was reminiscent of well-cooked pork or beef. The cloud ears had unfurled like huge fans. This dish, too, was pleasing to the eyes, with a slight red color resulting from the soy sauce, the mushroom water, or a combination of both, I supposed. I ate it with some rice I had boiled unceremoniously whilst working on the rest of the dishes.

As for the “Buddha Bowl,” there wasn’t much cooking to be done. I chopped some carrots and kale, boiled quinoa and frozen edamame, and mixed a dressing of soy sauce, sesame oil, rice vinegar, and brown sugar together. I also pickled some cucumbers and red radish in rice vinegar and brown sugar. The result was flavorful mostly by virtue of the dressing and pickled vegetables. It was also rather difficult for my stomach to process. Really, it is hard to think of something less congruent with the grammar of East Asian cuisine–tons of raw vegetables, roughly chopped, and eaten atop a grain originating from South America.[9] Nevertheless, eating it felt empowering, almost as if I was “accomplishing” the Buddha Bowl. A dish with so many raw vegetables and such an ascetic reputation must be healthy. And if my stomach felt like it was full of teeth–well, that was just part of the process.

Discussion & Conclusion: Authenticity, Translation, and Past-Past Nostalgia

While collecting my ingredients for the kenchinjiru, I was faced with an intriguing choice. The recipe called for Japanese seven spice powder, or shichimi togarashi, and Japanese sansho pepper, both listed as “optional.” I struggled with whether to include them. After all, I am not a Buddhist nun following the rules of Buddhist ascetic cuisine, and neither are most Japanese. The inclusion of these ingredients in the recipe spoke to the translation of Buddhist cuisine into “regular” Japanese cuisine over the years. My choice to exclude these spices, then, was a choice I made seeking some sort of authenticity. An adapted shōjin ryōri dish like kenchinjiru, of course, is oceans away from the food blasphemy that is the “Buddha Bowl.” But both dishes are capable of harnessing meaning from their origins, whether these origins are imagined or not. While researching Buddha Bowls, I was disturbed to read about the 2016 self-help book “Buddha’s Diet: The Ancient Art of Losing Weight Without Losing Your Mind.”[10] Meaning so easily becomes twisted. However, the pull of the past–of tradition, of “ancientness”–is powerful.

We are not alone in our obsession with the wisdom of the past, however. In the 13th century, prominent Zen Buddhist Dōgen wrote about how his tenzo peers had forsaken the righteous ways of the past. He encouraged these irresponsible tenzo, writing, “How can we fail by functioning as tenzo to actualize its marvelous nature and the Way in the same way those of ancient times did?”[11] These days, we find ourselves falling short in the same way that Dōgen saw his peers doing so. Dōgen’s invocation, then, is one of “past-past nostalgia,” himself a nostalgic figure invoking an even more distant past. What it is important to remember, then, is not that the past is illusory and forever out of our reach, though this may be true. It is that we will always be looking towards the past, just like the people who came before us did, adapting and re-translating stories, melodies, recipes, and ways of life. There is nothing wrong with a little shichimi togarashi in one’s kenchinjiru, just as there is nothing wrong with omitting it in an attempt to connect with a distant time. Authenticity, while perhaps overrated, is nevertheless meaningful. In the case of the “Buddha Bowl,” it is also a force to be wary of, since meaning can be appropriated to unsavory ends. For now, however, I will enjoy my kenchinjiru, my hongshao kao fu, and my Bowl, though it might be better to leave “Buddha” out of it.

[1] Namiko Hirasawa Chen, “Kenchinjiru (Japanese Vegetable Soup) (Video) けんちん汁” Just One Cookbook, Jan. 27, 2015, https://www.justonecookbook.com/kenchinjiru/

[2] “Homemade Chinese Wheat Gluten Mian Jin 自製麵筋,” The Hong Kong Cookery, Sept. 16, 2016, https://www.thehongkongcookery.com/2016/09/homemade-chinese-wheat-gluten-mian-jin.html

[3] Rachel Laudan, “Buddhism Transforms the Cuisines of South and East Asia, 260 B.C.E.–800 C.E.” in Cuisine and Empire: Cooking in World History. (University of California Press, 2013), 119.

[4] “Red Braised Wheat Gluten Kao Fu 紅燒烤麩,” The Hong Kong Cookery, Sept. 5, 2016, https://www.thehongkongcookery.com/2016/09/red-braised-wheat-gluten-kao-fu.html

[5] Rachel Tepper Paley, “Why Do We Keep Calling Things Buddha Bowls?” Bon Appetit, April 17, 2017.

[6] “Red Braised Wheat Gluten Kao Fu,” The Hong Kong Cookery.

[7] Hirasawa Chen, “Kenchinjiru.”

[8] Takeshi Watanabe, “Gifting Melons to the Shining Prince,” in Devouring Japan: Global Perspectives on Japanese Culinary Identity, edited by Nancy K. Stalker. (Oxford University Press, 2018), 50.

[9] Daniel Jurafsky, “Why the Chinese Don’t Have Dessert,” in The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu. (W. W. Norton & Company, 2014), 183.

[10] Katherine Sacks, “How the Buddha Bowl Got Its Name,” Epicurious, April 25, 2017.

[11] Dōgen, “Instructions for the Zen Cook,” in Cooking, Eating, Thinking: Transformative Philosophies of Food, edited by Lisa Heldke and Deane W. Curtin. (Indiana University Press, 1992), 16.